Introduction

Most of us grew up playing with a Nintendo 3DS, a handheld console from our childhood. But have you ever wondered what happens when you insert a cartridge into it ? Nintendo 3DS hide more than it seems, from their complex embedded system to their custom hardware and to their tactics of security and anti-piracy. This article aims to pull back the curtain on this intricate process, detailing the journey a game takes from being a physical cartridge to running seamlessly on your console, revealing the hidden layers of engineering and cryptography that define its operation.

Technical prerequisites and focus

To fully grasp the intricate details presented in this article, an understanding of specific technical concepts will be highly beneficial. While not exhaustive, familiarity with the following areas will significantly enhance your reading experience:

- Embedded Systems Basics

- File Systems: Knowing how data is logically organized, stored, and accessed on storage devices will aid in comprehending the various partitions and data structures discussed.

- Binary Formats: The article delves into the internal structure of executable code and data files. A basic understanding of how software is compiled and structured in binary form will illuminate discussions on code loading and execution.

- Cryptographic Fundamentals: Concepts such as encryption, decryption, and digital signatures are central to the 3DS’s security. A grasp of these principles is essential for understanding how the console protects its games and firmware.

This article will mainly focus on the Nintendo 3DS cartridge’s lifecycle, from its initial detection by the console to the secure execution of its game code, exploring its unique hardware elements and communication protocols. To contextualize Nintendo’s significant advancements in security, we will also briefly examine Nintendo DS/DSi cartridges. This comparative analysis will highlight how their simpler detection, initialization, and hardware layouts contrast with the 3DS’s protective measures, underscoring Nintendo’s direct response to the vulnerabilities inherent in earlier console generations.

Cartridge detection and initialization

A Nintendo 3DS cartridge uses a 17-pin interface. Each pin has a distinct role, including power (VCC), ground (GND), reset (RST), and chip selection lines RCS for ROM, ECS for save. Internally, the cartridge typically contains a ROM NAND, an Actel/IGLOO chip and an EEPROM. [1]

When a cartridge is inserted, the console uses a mechanical detection mechanism. A small internal switch inside the console is triggered. It is connected to a GPIO input, readable through the CFG9_CARDSTATUS register of the console. The first bit value is set to 1 to indicate that a cartridge is inserted. Then the second and third bits of the CFG9_CARDSTATUS register are set to 10, to enable the VCC pin. [2]

Once the cartridge is powered, the console sends a reset signal with the command 9F 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 which

will assert the RST pin low. This will put the cartridge in a known state (for security and to avoid bugs).

After that, it will read the first bytes of the cartridge header.

If it detects that it is a DS game, the console reloads itself into a DS environment emulated. When such a cartridge is detected, the 3DS disables most of its modern features and boots into DS mode. The ARM7 and ARM9 processors take over, mimicking the DS execution environment.

If the cartridge is identified as a 3DS game, the command 71 C9 3F E9 BB 0A 3B 18 is sent to instruct

the cartridge to operate in 3DS protocole mode as it does not know with which protocole to work. In response,

the console requests two identifiers, the Card ID1 (chip ID) and Card ID2 (chip type). [3][4]

It initializes a 16-byte command mode for communication: 3E 00 00 00 00 00 00 00.

The console gets data like the NCSD header that defines the layout of encrypted partitions on the cartridge. [5]

Authentication and mounting

As previously noted, the initialization for DS’s cartridges is simpler. DS games don’t use signatures or encryption. As a result, the cartridge’s contents can be read and executed directly, making them less secure but more straightforward. The cartridge header is read directly and is mounted in a sandboxed environment.

From here, for 3DS cartridges, encryption is enabled and each command send must be decrypted. The console needs to verify the authenticity of the game and decypher its content.

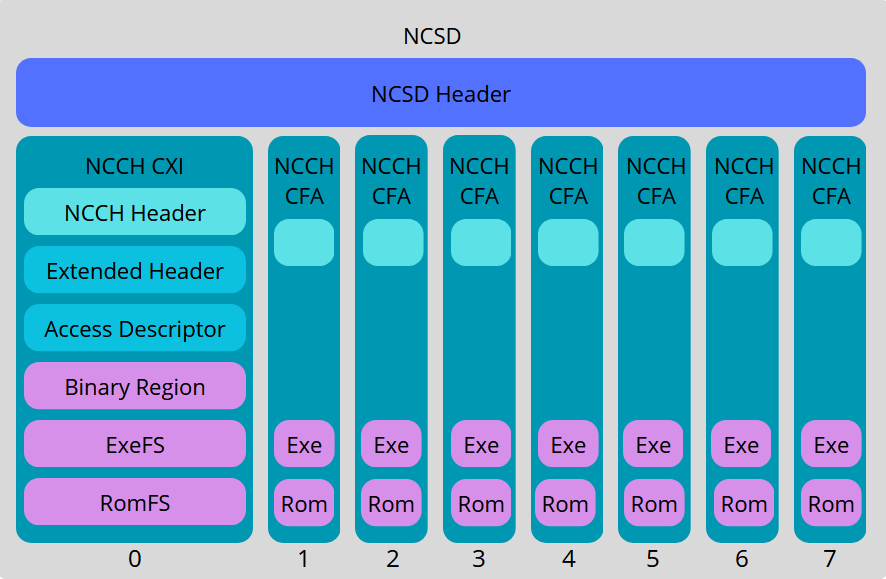

NCSD is a container format of Nintendo 3ds. One of its specialisation is the CCI format (CTR Cart Image, CTR is the code name of 3DS) which is the format of game ROM images. NCSDs start with a header, followed up by a maximum of 8 NCCH partitions. NCCH partitions can be of two formats : CXI (CTR Executable Image) and CFA (CTR File Archive). The first partition is in CXI format and is reserved for the executable content. That is where the game is stored. The others NCCH partitions are in CFA format and used as a complement to the first partition. What is in purple signify that it is optional. [6][7][8]

NCCH contains a digitally signed header. This 2048-bit RSA signature covers the partition’s metadata, including offsets, sizes, and flags. The public key needed for verification is embedded within the 3DS system firmware, making this a one-way trust chain that relies on Nintendo’s private signing infrastructure. Once the authentication is confirmed, the console initalizes the decryption process.

The cartridge’s contents are encrypted using AES-CTR with 128-bit keys. The Nintendo 3DS uses an encryption engine with 64 keyslots. Each slot can contain a temporary or persistent 128-bit AES key, used to encrypt or decrypt sensitive data such as games.

Decryption needs two inputs, the KeyY, derived from the title ID, and the KeyX typically stored

in the slot 0X2C of the console. [9] KeyX is written in the boot ROM of the console and KeyY is written in the

cart at the factory, when they are made.

These values are fed into the hardware AES key generator which produces a NormalKey.

This key is loaded and used for decryption of game data.

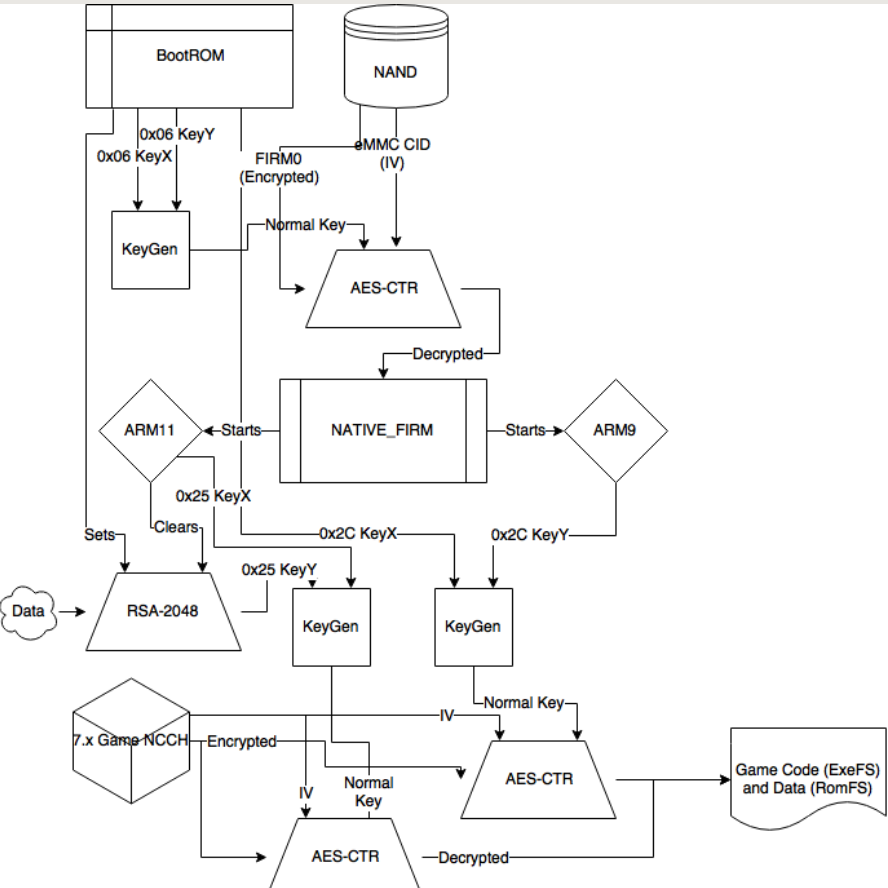

[11]

[11]

This diagram explains how it works. The block “Game NCCH” represents the game as it is stored and distributed. It is fully encrypted for security reasons and to protect against piracy. To access the game, the console’s internal system initiates an AES-CTR decryption module. This module requires two key elements:

- An IV

- A Normal Key

The IV (Initialization Vector) is a non-secret, unique value for each encryption operation. In the context of the 3DS, this IV is often derived from a block counter or a unique identifier associated with the data being decrypted, ensuring that identical plaintexts result in different ciphertexts, enhancing security.

The diagram shows that the Normal key is dynamically generated by a Key Generator using “0x2C KeyX”

and “0x2C KeyY.” These KeyX and KeyY are deep system keys, controlled by the NATIVE_FIRM firmware and

the console’s ARM processors (ARM11 and ARM9).

NATIVE_FIRM is the primary operating system of the 3DS, residing in a secure area of the console’s internal

memory. It is responsible for managing core hardware functions, security policies, and providing the low-level

services that applications like games utilize. This design ensures that only a genuine Nintendo 3DS system

running a valid firmware can generate the “Normal Key” and decrypt games.

The diagram is a simplification of the complex security system of the 3DS. That’s why it doesn’t show that

the Normal Key used to decrypt the contents of a set is a combination or derivation of one of

the system’s general keys (0x2C KeyX/0x2C KeyY) and the set’s unique Title ID.

Once the AES-CTR process has been successfully completed, the encrypted NCCH container is transformed into a format that can be read and used by the console. This output is divided into two main parts :

-

The game Code, ExeFS, which is the Executable File System, containing the game’s binary code. This is what the console’s ARM processors will load and execute to run the game. [12]

-

The Data, RomFS, which is the ROM File System, containing all the game’s non-executable resources, such as graphics, textures, 3D models, audio tracks, dialogs, level data, and any other assets required by the game. [13]

Those partitions are virtually mounted and the system creates virtual pointers towards them for the user process.

Nintendo strengthened the cartridge security on the 3DS as a direct response to the vulnerabilities of the Nintendo DS gamecards. DS cartridges were unencrypted and lacked any meaningful authentication, making them easy targets for piracy and homebrew development. Cloned cartridges and ROM flashcards became widely available, undermining the commercial ecosystem. To counter this, Nintendo redesigned the 3DS cartridge system to include secure hardware elements. All the new protocols of security made it extremely difficult to clone, tamper with, or spoof a legitimate 3DS gamecard. The goal was to enforce authenticity at the hardware level and ensure that only Nintendo-approved games could be loaded and executed on the system. But now we know that despite all those ideas, it was not enough to stop people from homebrewing their console.

Process creation and code loading

Now that the game data is authenticated and decrypted, the Nintendo 3DS can prepare the code execution within an isolated process in its operating system. This involves several critical steps to transition the static game data into a dynamic, running application.

First, the decrypted ExeFS (containing the game’s executable code) and RomFS (containing game data assets) must be loaded from the cartridge’s NAND flash into the console’s RAM (Random Access Memory). Unlike NOR flash, NAND flash is not typically suitable for direct code execution thus, the game’s code is copied into the RAM, which is faster, for the ARM processors to access efficiently. The Memory Management Unit (MMU) plays a crucial role here, managing these memory allocations and establishing virtual address spaces unique to the game’s process. This ensures that the game operates within its designated memory boundaries, preventing conflicts with other system processes or sensitive data. [14]

Next, the 3DS operating system creates a new, isolated user process specifically for the game. This process is a self-contained environment with its own virtual address space, CPU registers, and an initialized state including its stack and instruction pointer. The game’s code is loaded into this newly allocated memory. The console’s ARM processors, operating in user mode, then transfer control to the game’s entry point typically a main function or an initial setup routine within the ExeFS. The game’s initial actions will involve setting up its own logic and loading preliminary resources from the RomFS into RAM as needed. [15][16]

Game execution and System Security

Once started, the game process operates within a strict sandbox environment, that is to say a closed environment applying strict restrictions. This sandboxing is a critical security measure. It prevents the game’s code from executing unauthorized instructions or directly accessing sensitive areas of memory belonging to other processes, the console’s firmware, or privileged hardware components. This isolation ensures system stability, prevents malicious software from compromising the console and protects user data.

Since the game process is sandboxed and isolated from the rest of the system, it cannot directly access system resources or other processes’ memory. To interact with the operating system and system services, the game relies entirely on Inter-Process Communication (IPC) mechanisms. The primary method of IPC on the 3DS is through Supervisor Calls (SVCs). An SVC is essentially a software interrupt that allows a user-mode process (the game in our case) to request a service from the kernel. For instance, if a game needs to access Wi-Fi, save data, render graphics, or interact with sensors, it makes a specific SVC call. The kernel then meticulously filters and validates each SVC request, permitting only authorized operations with appropriate parameters. Any attempt to use an unauthorized SVC or provide invalid parameters will cause the game process to crash, which is a built-in security mechanism to prevent exploits. This IPC-based communication forms the backbone of the interaction between the sandboxed game environment and the system.

While the 3DS is not a full-fledged multitasking system like a PC, its OS does manage multiple processes concurrently including the game itself, various system services, and the Home Menu. The operating system is responsible for allocating CPU time and other resources to the game like the memory or the peripherals. Game processes typically run at a lower priority compared to critical system services, ensuring the console’s core functions remain responsive. (This behavior is derived from reverse engineering efforts, notably by 3DBrew and researchers, and not officially documented by Nintendo.)

At this stage, with the game’s code loaded, authenticated, and running within its secure environment, the user can now fully interact with and play the game. [15][17][18]

Conclusion

The game launch process on the Nintendo 3DS shows the necessity of secure software practices in embedded systems engineering. From physical insertion to cryptographic authentication and isolated execution, each step ensures that only verified, legitimate software is allowed to run. Nintendo’s shift from DS to 3DS cartridges marked a turning point in their hardware security model. The addition of RSA-based authentication, AES encryption, and protocol-based cartridge communication turned gamecards into smart, secure tokens. At the same time, compatibility with DS/DSi games was preserved through processor emulation.

However, despite these robust security measures, the system eventually faced challenges from the homebrew community. Exploits that managed to bypass these sandbox mechanisms, often by finding vulnerabilities to gain kernel privileges, allowed for the execution of unsigned code and homebrew applications. This demonstrates the continuous cat-and-mouse game between platform security and reverse engineering efforts. By dissecting this process, we gain insight into broader embedded topics.

Our detailed exploration of the Nintendo 3DS’s game launch highlights a remarkable evolution in console security and embedded system design, a testament to Nintendo’s continuous push for innovation across its hardware generations. The principles observed here, from cryptographic authentication to isolated execution environments, have been refined and reimagined in every console Nintendo has brought to market, each offering a distinct yet equally compelling tale of engineering. The 3DS remains not only an iconic portable entertainment but also a case study in secure embedded design.

Bibliography

Quoted in the article:

- [1] https://www.3dbrew.org/wiki/Gamecards#Physical_interface

- [2] https://www.3dbrew.org/wiki/CONFIG9_Registers

- [3] https://www.3dbrew.org/wiki/Gamecards#Protocol

- [4] https://problemkaputt.de/gbatek-3ds-cartridge-registers.htm

- [5] https://www.3dbrew.org/wiki/NCSD#Card_Info_Header

- [6] https://problemkaputt.de/gbatek.htm#3dsfilesncchformat

- [7] https://www.3dbrew.org/wiki/NCSD

- [8] https://www.3dbrew.org/wiki/NCCH

- [9] https://www.3dbrew.org/wiki/AES_Registers

- [10] https://blog.winter-software.com/2024/06/02/ctr-cart-protocol

- [11] https://yifan.lu/2016/04/06/the-3ds-cryptosystem/

- [12] https://www.3dbrew.org/wiki/ExeFS

- [13] https://www.3dbrew.org/wiki/RomFS

- [14] https://www.3dbrew.org/wiki/Memory_layout

- [15] https://www.reddit.com/r/3dshacks/comments/6iclr8/a_technical_overview_of_the_3ds_operating_system

- [16] https://douevenknow.us/post/175244491263/nintendo-and-executables-emulation-and-piracy

- [17] https://www.3dbrew.org/wiki/SVC

- [18] https://www.3dbrew.org/wiki/IPC

Others used: