Introduction

As the complexity of modern devices grow, we need simple and efficient ways to view our complex system’s states and events. How can we be certain about what’s really happening in our programs? We somehow need to convey some sort of feedback trough a communication medium to an external observer. With enough knowledge about the system, the observed events and the environmental context, one can examine and analyse the behaviour of the program over time.

Keeping an history of these events is crucial in troubleshooting. Black boxes on airplanes are one such example. Valuable flight data and cockpit voices are recorded. It provides unique informations in understanding the chain of events which lead to a crash, potentially saving thousands of future lives.

Logging is one way of opening a window in our blackbox devices running at absurdly high speeds.

What is deferred logging

Old school embedded logging techniques

One of the simplest form of logging is our beloved printf.

It’s interface is very straight forward and easy to use.

The user crafts a string literal containing format specifiers which are replaced by the function parameters, in order, when printed.

It also has advanced features such as:

- left/right alignment

- left padding by spaces or zeros.

- floating-point precision

- sized strings

- and many more…

Up to the point that printf is accidentally Turing-complete!

On Linux, the printf function writes the formatted output the program’s stdout.

However, on microcontrollers such as STM32s, there is no concept of stdout.

Most of the time, the libc syscall stubs are dummy functions with custom implementations depending on the platform.

For example, here a small portion of the file syscalls.c in a STM32F429 project:

|

|

Notice that:

- the

fileparameter is complety ignored troughout the file - the

_writefunction no longer performs a syscall and calls to an external__io_putcharfunction. - the

__attribute__((weak))which allows anyone to write its own implementation of_write.

Most of the time, we’ll write our own __io_putchar to redirect the logs trough a physical communication medium.

Such communication medium could be UART, SPI, ITM (ARM Cortex-M Instrumentation Trace Macrocell), USB CDC, RTT (based on RAM) and many more.

One other option is to store them in a local storage medium to save them for later. The storage mediums typically used for logs are RAM, EEPROM (internal or external), SD Cards, eMMC and more!

Deferring the formatting to the host

As our machines become faster and faster, we generally don’t think anymore about the cost of printing and formatting strings. However, on a small embedded microcontroller, this cost can be quite high:

-

High CPU usage or waiting for IO operations to complete can pause critical code execution in real-time applications, increasing system latency and making it less deterministic.

The latency can be crucial depending on the application : under/overshooting in a closed feedback loop (e.g. PID), display stuttering, missed task deadlines, and more.

-

Increased power consumption : formatting the strings and transmitting them over the wire when no one is listening is a waste of CPU time and, thus, battery power.

-

Code size : printf’s runtime string processing is not designed to be space efficient. Here are some size measurements of the sample projet used in this article:

C std library printf used printf float support Code size (-Os -Wl,–gc-sections) newlib no - 5201 (A) newlib yes no 10657 (A+5.5KB) newlib yes yes 27061 (A+21.8KB) newlib-nano no - 4993 (B) newlib-nano yes no 7401 (B+2.4KB) newlib-nano yes yes 19129 (B+14.1KB) These numbers are for illustration purposes only as I did not spend enough time carefully isolating the printf code size. Furthermore, the sample projet contains little to no code.

-

IO Bandwidth : Traditionnal logs consists of human-readable ASCII (or UTF-8) messages of variable size. The same messages can be sent several hundreds of times over a small time period. Thus, consuming a lot of IO bandwidth to transmit recurring logs.

How can we solve all this issues?

If there is at most N distinct log messages, then log2(N) bits is enough to uniquely identify each one.

Thus, instead of transmitting the formatted string every time, we can send a log unique ID alongside the format parameters.

The simplest form of unique ID, in software, is a pointer, as only a single string/instruction can be stored at a specific address.

Note that pointers are not memory efficient unique IDs as a lot of possible pointers are not valid, for example, pointing in the middle of an instruction or a string.

For example, consider a 1KB section containing 34 strings, a pointer must be at least 10 bits to address any byte in the section. However, 34 strings can be uniquely addressed by 6 bits (

2^6 = 64possible values).

The idea is very simple : instead of sending the string contents, send the string’s pointer as the log unique ID. The host, receiving the logs, will build a map of pointers to log messages once and formats the incoming logs on the fly.

Compared to the previously mentionned costs:

- Lower CPU time when logging, as most of the CPU time is spent formatting the string.

- Lower power consumption, as no formatting is computed.

- Smaller code size, as we no longer need to embed the formatting logic.

- Lower IO bandwidth, as only the few necessary bytes are transmitted.

Let’s try a small logging library implementing this idea.

Digging Deeper

Writing a printf clone

The goal is to make the library easy, convenient and transparent for the users.

Let’s try to recreate our own limited version of what we are all familar with, printf!

Note that C variadic functions do not have any count or type information on the function parameters. In the case of

printf, these properties are stored in the string itself through the format specifiers.

First, all the platform-specific code for sending bytes will handled by the user-defined function

|

|

To keep the code concise and simple for this article, trunkf will only support the signed integer format specifier %d.

This way, we have to implement only two serialization functions:

|

|

Here is the first implementation of the trunkf variadic function:

|

|

Then the user can easily replace calls to printf with trunkf:

|

|

On the host side, the transmitted bytes looks like:

| string pointer | 1st parameter | 2nd parameter | 3rd parameter |

|---|---|---|---|

d0 65 00 80 |

01 00 00 00 |

02 00 00 00 |

03 00 00 00 |

With traditionnal logging, at least 33 bytes will be transmitted, as the integers have a varying number of digits.

With deferred logging, we are transmitting only 4 + 3 * 4 = 16 bytes.

Compile-time variadics using the C11 preprocessor

Still, our implementation is quite CPU intensive as the format string must be scanned to locate the format specifiers.

Can we locate the format specifiers at compile time?

The location of the format specifiers is only used by the host to format the logs. However, the type information embedded in the format specifiers determines how should we transmit the format parameters. Let’s try to extract the parameters’ type at compile time.

First, we’ll define a macro that dispatches each function parameter to the correct serialization function depending on its type.

The C11 standard has introduced the keyword _Generic used to select an expression based on the type of an another expression.

The type of the first argument to _Generic will determine which expression in the second argument, the type list, will be used.

This feature makes the implementation of the macro trunkf_send possible:

|

|

The C preprocessor will expand:

trunkf_send(1)totrunkf_send_u32(1)as 1 is typed, by default, as int.trunkf_send((uint8_t)1)totrunk_send_u8((uint8_t)1).

Next step, rewrite the trunkf variadic function as a macro:

|

|

Notice that:

- The

do { ... } while (0)is a common construction used to ensure that the macro behaves like a statement and not an expression. - The argument

Messageis enforced to be a string literal by the compiler. Two consecutive string literals are concatenated together at compile time. This is required as we rely on the pointer to be located in the binary. - The

trunkfmacro does not scan strings anymore but at the cost of additional instructions and thus greater code size. - There is no additional format type safety, as with

printf. If a format specifier does not match the actual parameter type, the behaviour is undefined. - The

trunkfmacro accepts exactly 3 values for format specifiers.

To lift the last limitation, we’ll make the trunkf macro variadic again:

|

|

Remarks:

- The

__VA_ARGS__macro stores the rest of the arguments. For example,__VA_ARGS__will expand to1, 2, 3intrunkf("Msg", 1, 2, 3). - The

TRUNKF_FOR_EACHmacro calls the__trunkf_evalmacro on each argument (if there is any). The only purpose of__trunkf_evalis to maketrunkf_sendbehave like a statement.I will spare you the details of the

TRUNKF_FOR_EACHmacro, taken from Macro Metaprogramming. To keep the implementation simple, I limited the number of parameters to 16.

With the previous example, the code

|

|

will be expanded to

|

|

The original printf slowly transformed into a sequence of send calls.

Opening the possibility of storing an history of these compact logs on device.

Synchronization and Escaping

In theory, everything seems to be fit together just fine. In practise, the first issue comes up when the logs are being flooded. It’s difficult to know when to start interpreting the raw binary stream correctly because:

-

The string pointers determines the number of following format parameters.

-

A random sequence of bytes can be a valid string pointer. For example:

string pointer 1st parameter 2nd parameter d0 65 00 42-- -- -- d065 00 50 --If we start reading from the last byte of the 1st parameter, the value

d0 65 00 50is a valid string pointer, pointing atoriginal string+8.

The decoder need to be synchronized on a specific symbol or pattern.

One solution is to introduce a start of frame symbol.

Let’s use the magic value 0x42 as an escape symbol.

The escape sequence is composed of two bytes, representing:

- a start of frame symbol, if the following byte is

0x00 - a byte

0x42, if the following byte is0x43

For example, a call to trunkf("%d\n", 0x42); with the string pointer 0x420065d0 will produce:

| SOF | string pointer | 1st parameter |

|---|---|---|

42 00 |

d0 65 00 42 43 |

42 43 00 00 00 |

This way, the decoder can easily distinguish the start of a frame symbol from the format parameters. Let’s make the following changes:

|

|

|

|

This solution is not optimal because:

- It has some CPU overhead as every single byte must be checked and escaped if necessary. It also makes processing and sending bytes by batches harder, preventing IO operations speed ups.

- The escaping sequence is not space efficient.

Two bytes are used for the start of the frame.

One more byte per escaped

0x42. In the worst case, all bytes are0x42which doubles the frame length. This overhead can be greatly improved by using a better algorithm, such as Consistent Overhead Byte Stuffing.

Stripping the section from the binary

The trunkf no longer relies on the format strings’ contents to be accessible.

Therefore, all format strings can be stripped from the flashed binary, further reducing its size.

Let’s create a section .trunk only for strings!

To do that, we have to enter linker script territory.

A linker script is a configuration file for the Linker.

It describes how the ELF executable is assembled.

This is required to satisfy the C ABI making our binary run on the target.

Thankfully, we don’t need to write one from scratch as the STM32F429 sample project already has two.

First, the format string literals are required to be stored into that section:

|

|

Small note on

static:In this case, when a variable is assigned a specific section, it must have a unique symbol in it. By default, the variable’s name is exported as its symbol. When the user tries to use the macro multiple times, the symbol

__trunk_msgwill get declared multiple times!To prevent this, we use

staticto limit the symbol to the current scope. The linker automatically appends a suffix.X, where X is a counter, to keep the symbol unique.

In the following linker script:

- the

KEEP(...)tells the linker to keep the data in this section even if not referenced anywhere in the binary. - the

> FLASHdetermines the storage region (where is the data being stored).

.section_name :

{

KEEP(*(.section_name))

} > FLASH

In our case, the section .trunk should:

- Not be flashed and thus not placed in any storage region.

- Not be mapped into memory (e.g. RAM).

- Contained in the ELF binary so we can retrieve the strings content later.

Thus, the only piece to append to the STM32F429ZITX_FLASH.ld linker script is:

.trunk :

{

KEEP(*(.trunk))

}

Decoder

Extracting strings

Now, the STM32F429 spits out random binary data through UART to the computer. Like the library, the tooling must have a simple user interface:

|

|

The decoder takes a single argument, the ELF running on the STM32F429. After loading the strings, stdin’s data will be decoded and formatted to stdout.

Let’s extract the strings by hand before implementing the decoder:

|

|

Thankfully, on linux, the header elf.h defines all the ELF32 and ELF64 types and structs.

In the case of STM32F429, an ARM Cortex-M CPU, the decoder parses an ELF 32-bit executable.

I spare you the C file reading and .trunk section searching boilerplate code.

If found, the decoder reads the section’s start address and ELF file offset.

The section’s content is scanned to find all null-terminated strings.

A global dynamic array will store all found string copies:

|

|

Last but not least, the main loop:

|

|

The read_frame function will:

- Confirm or reject the possible start of frame.

- Read and find the string pointer in the

TrunkStringsarray. - Scan the format string to extract the format specifiers.

- Print the formatted message using the incoming format parameters.

- Update the

BufferedReaderstruct to process the remaining binary stream.

Final result

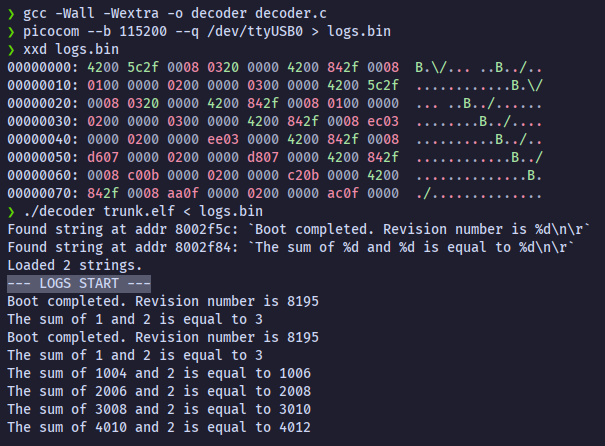

Offline decoding

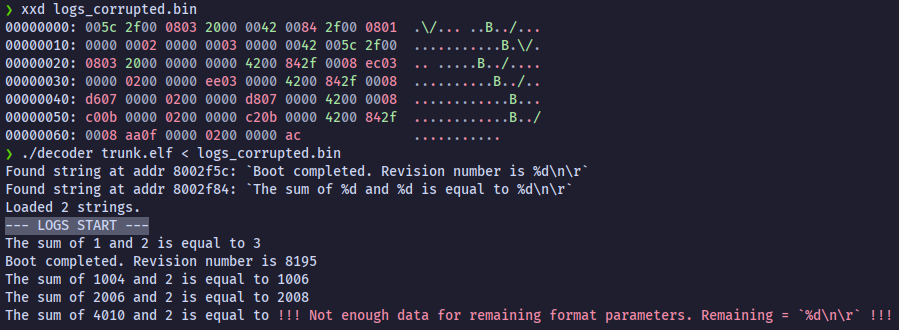

Offline decoding of a corrupted dump

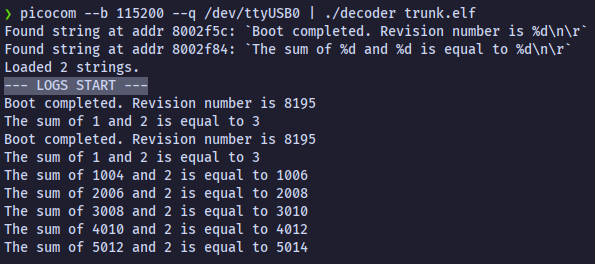

Live decoding

Tadaa! The whole log chain works!

Benchmarks

I ran some simple benchmarks to compare printf and trunkf. The benchmark consists of logging one message as many times as possible for exactly 1s:

|

|

The code was compiled with -O2 and is running at 170Mhz on the Cortex M4 CPU Core.

The 32-bit hardware timer TIM2 is used to stop the execution after exactly 1s (or 170000000 clock cycles).

The data is sent, byte per byte, through UART connected to the ST-LINK probe.

First run is using UART baudrate of 115.200 Kbit/s:

| trunkf | printf (i =) | printf (call nb) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total calls | 1138 | 1232 | 874 |

| Total bytes received through UART | 11408 | 11174 | 11282 |

| Total IO time (total_bytes*10/baudrate) | 990.3 ms | 970.0 ms | 979.3 ms |

| Total compute time (1s - Total IO time) | 9.7 ms | 30.0 ms | 20.7 ms |

| Avg Compute time per call | 8.5 µs | 24.4 µs | 23.6 µs |

A UART byte is transmitted as 1 start bit followed by 8 data bits and ends with 1 stop bit. Thus transmitting one byte takes

10*1/baudrateseconds.

Notice how printf with the smalller message has more calls than trunkf despite the higher compute time per call.

This result can be explained by the amount of bytes transferred by both methods.

A trunkf frame is composed of 10 bytes but the actual message is only 7 bytes.

At this baudrate, one byte takes 86.806 µs which is >3.5x than printf’s compute time per call and 10x trunkf’s.

All three test cases show that the IO time represents >97% of the total test time.

We can’t conclude yet on the compute time per call as this run is bottlenecked by IO.

Lets try to increase the baud rate to 921.600 Kbit/s and see what happens:

| trunkf | printf (i =) | printf (call nb) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total calls | 8608 | 7838 | 5730 |

| Total bytes received through UART | 86130 | 77266 | 79148 |

| Total IO time (total_bytes*10/baudrate) | 934.6 ms | 838.4 ms | 858.8 ms |

| Total compute time (1s - total IO time) | 65.4 ms | 161.6 ms | 141.2 ms |

| Avg Compute time per call | 7.6 µs | 20.6 µs | 24.6 µs |

However, after increasing one more time the UART baudrate to 1.843200 Mbit/s, the results didn’t change much and are proportionnal to the doubled baudrate:

| trunkf | printf (i =) | printf (call nb) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total calls | 16184 | 13171 | 10002 |

| Total bytes received through UART | 161923 | 133802 | 138955 |

| Total IO time (total_bytes*10/baudrate) | 878.5 ms | 725.9 ms | 753.9 ms |

| Total compute time (1s - total IO time) | 121.5 ms | 274.1 ms | 246.1 ms |

| Avg Compute time per call | 7.5 µs | 20.8 µs | 24.6 µs |

We can conclude that:

- At low IO speeds, when sending one byte takes longer than the computing time, the test is IO-bound. Sending less bytes translates to lower overall execution time and thus more logs.

- At higher IO speeds, sending bytes still takes up to <87% of the total time but the compute time is no longer negligible.

- printf’s total execution time (compute+IO) is proportionnal to the length of the transmitted message.

- trunkf’s no-processing strategy only pays off when the number of bytes in the frame is lower than the length of the message.

- This implementation of Deferred logging uses, on average, 2.77x less compute time than printf’s best case scenario (very small messages).

- In real world applications, logs are much longer and may use more format parameters. Further testing is required to assess how the two methods scale up.

Though, one could improve the peformance of both logging methods by transferring data more intelligently by software (ex: buffers, batching) and/or by hardware (ex: DMA).

Comparing the binary size

Last but not least, let’s compare the two tests (trunkf and printf with i = ...) flashed binary size:

| text | data | bss | total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| printf | 13172 | 104 | 2136 | 15412 |

| trunkf | 9144 | 12 | 1796 | 10952 |

Both tests were compiled using -Os and newlib-nano without printf float support.

The trunkf flashed binary size is 4.46 KB smaller.

Limitations

Versioning

One limitation of this implementation of deferred logging is the stability of the string pointers. Indeed, some format string pointers may change between two compilation rounds. Adding a single character to the string at the beginning of the section will change all following string pointers. The decoder always needs the latest running binary to decode any log message.

There is two possible solutions not covered in this article:

-

Add a

versionfield in every frame to identify the device firmware’s version. It’s very common to have lots of coexisting firmware versions in the wild. The firmware maintainers should maintain a database of the log message bindings for every published version.Though, it introduces some overhead as the version is unlikely to change during a log session. 10 to 12 bits of the string pointer’s 4 bytes can be reserved for a version, at the cost of reducing the number of strings.

-

Use more stable unique IDs using

checksumsorhashing. Indeed, the checksum or hash of a string only depends on it’s content. Changing one character of a string only changes its own ID.It is very difficult to implement this at compile time in C23, the latest C standard. An external program with the corresponding compilation step can be introduced.

This approach allows the decoder to work with older log message bindings. However, with 32-bit hashes, the probability of collision is a quite high and should be carefully considered.

Access to the binary

What happens if we don’t have access to the Debug/trunk.elf ?

Nothing! It’s simple : no .trunk section, no logs.

It’s a big limitation of this logging approach.

We can’t just dump the device’s firmware image. Indeed, by design, the strings are not contained in the flashed binary. On the positive side, it provides free obfuscation of the log messages. Any user, or hacker, can’t easily sniff the UART wires to spy on the logs. Though, one with enough time and resources can reverse-engineer the format. Some information can also be inferred from the frequency of the log messages.

I’ll recommend looking at encryption, at this point.

One possible solution is to publish the log message bindings. But don’t expect anything from closed source firmware. Companies can decide to not share them with the consumers. Which results in frustration for a user trying to diagnose or repair their device.

The other binary required is the decoder. If the logger uses an other framing algorithm, the decoder must know about it. Everyone is free to develop their own protocol and binary format. Thus, restricing access to the decoder is also problematic for the end user.

Conclusion

Logging is everywhere in today’s software applications. Many devices log events using human-readable messages through a communication medium. However, recurring log messages have a significant cost. Formatting takes CPU time, long messages use more IO bandwidth. The formatting code must also be included in each program.

Deferred logging tries to solve all this problems with a simple idea. Transmitting message IDs instead of string-based events. The host’s CPU will take over by formatting the logs on-demand. The formatting code and the string messages no longer need to be stored on device. Thus, reducing the CPU, RAM and Flash requirements and increasing battery life.

The first limitation is the more complex decoding process. One can also purposely restrict the access to the log message bindings. The second limitation is identifiying which language is the device speaking. As the transmitted message IDs are highly coupled with the firmware’s code. Version numbers or more stable unique IDs can relax this coupling. Allowing different versions of firmware and decoder to understand each other.

Thanks for reading!

Biography

- Similar open-source projects

- In C

- Trice and its detailed presentation article

- elog

- In C++

- In Rust, defmt.

- In C

- Writing linker script:

- Tips for Using Printf on Embedded devices

- C Preprocessor

- Consistent Overhead Byte Stuffing

- Advanced catalog logging in Intel desktop chipset driver at CppNow 2022.