Introduction

“Funky” file formats depart from the usual rule whereby a file’s extension indicates its format and tells you what it contains without hiding anything else. In a polyglot file, the same bytes can validly be interpreted as two (or more) different file types or different file contents with same type. These exotic files may look innocent but secretly carry hidden data or code. The ability to construct these multi-headed files is not just a hacker’s toy. It can reveal surprising weaknesses in file specifications and can expose how programs trust file structure.

This article is inspired by Ange Albertini’s work on Funky File Formats. Albertini is a reverse engineer and file-format expert (creator of the Corkami project for dissecting formats) who has demonstrated many creative format-abuse techniques. He also introduced “AngeCryption”, an AES-based method to force an encryption routine to output a valid desired file format.

This article will offer a clear and accessible explanation of polyglot files and Angecryption, even for beginners. What they are, Why they matter, How they work and How to build them. Readers will learn both the what and the how behind these binary magic tricks.

Recap: AES Mode

AES encrypts data by applying a series of transformations to small blocks of information (128 bits at a time). It repeats the same steps several times (called rounds) to make the data completely unreadable without the correct key.

- SubBytes -> replaces each byte with another (like a secret lookup table)

- ShiftRows -> shifts rows to mix up data

- MixColumns -> combines bytes in columns to spread patterns

- AddRoundKey -> mixes in part of the secret key

The same key is used in reverse to decrypt and get back the original message.

What Is a Polyglot File?

A polyglot file is one that simultaneously conforms to two or more file-format specifications. In practice, this means the same sequence of bytes can be parsed as valid by multiple ways. For example, a single file can be interpreted both as a valid image and a valid ZIP archive, depending on how you open it.

How to Build Polyglot Files

Creating a polyglot file requires intimate knowledge of the file formats involved. In general, one exploits features like: magic headers, chunk or section markers, ignored/optional fields, and tolerance to extra data. The Corkami/Mitra projects summarize several common layout tricks:

-

Stacks (Appended Data): Attach one file after another. Many formats simply ignore anything after a valid end-of-file marker. For example, PNG images will still display even if extra bytes follow, and JPEGs ignore data after their EOI (End-of-Image) marker. This means you can append a ZIP, PDF, or script to the end of an image and have a single file that is both.

-

Cavities (Space Reserves): Some formats have unused “dead space” or padding you can manipulate. For instance, certain image or video formats allow appending comment chunks or alignment padding. You can hide data there without breaking the primary format.

-

Parasites (Comments): Many formats have comment or metadata sections that are essentially freeform. For example, one can stick arbitrary text or code inside HTML comments. The file still appears normal (the comment is ignored by, say, a PDF viewer), but the hidden content can be extracted or executed by another engine.

Other well-known techniques exist, and links to further information are provided at the end of the article.

Polyglot example

Imagine combining PNG and ZIP via stacking: we take a normal PNG file (with its signature and chunks ending in IEND), and then concatenate the bytes of a ZIP archive right after the PNG’s end. Because PNG readers stop at IEND, the image remains valid.

Meanwhile, ZIP tools (which search for PK\x03\x04 structures anywhere in the file) find the ZIP data and open it. The combined file is thus both a picture and an archive.

[ PNG signature + chunks + IEND chunk ] [ ZIP file header "PK.." + ZIP data + central directory ]

However, it would be too easy for it to work like that: there are a few subtle changes to make in our zip file for it to be valid.

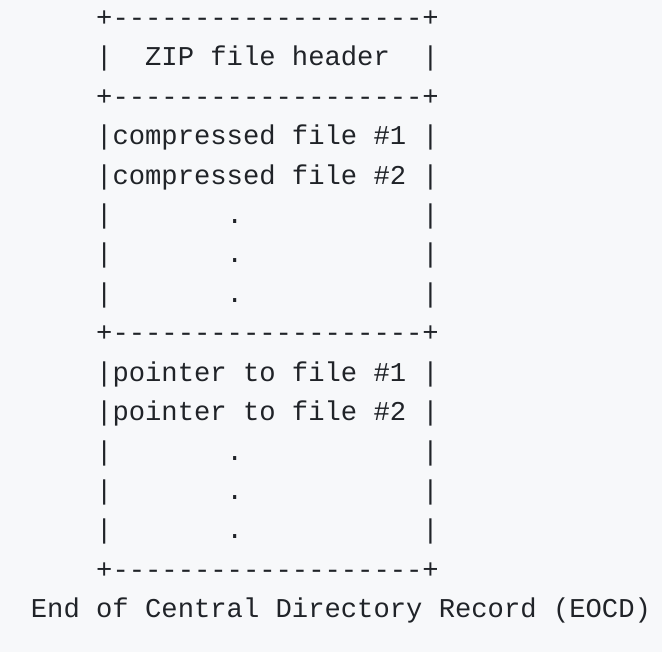

ZIP format:

[ ZIP file header "PK.." + ZIP data + central directory ]

with more details on ZIP:

For example, if you add a zip after an image of 2400 bytes, all you have to do is add 2400 to all pointers to data. And you’re done.

Going further…

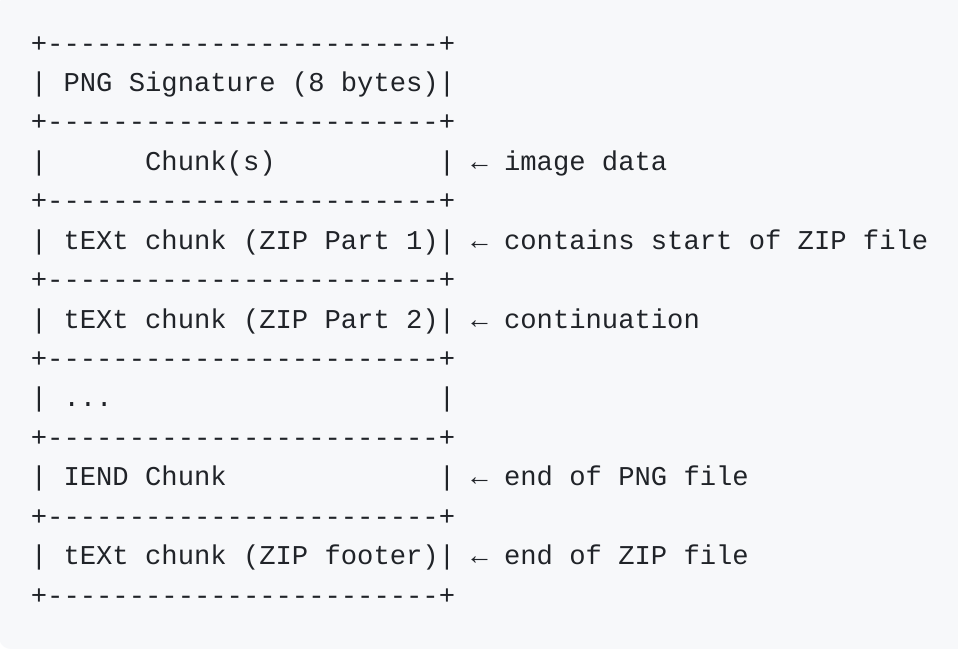

It would be safer not to add too many bytes after the image, as some parsers might not like it. One thing we can do is to include the ZIP data in the comment blocks of our PNG. A PNG file is a list of chunks. Each chunk is composed of its size, its type, its data, and the end of the chunk. Here, we’ll be focusing on the tEXT type, which can be used as a comment in a PNG.

Chunk in PNG:

[Length: 4 bytes]

[Type: 4 bytes] -> tEXT for comment

[Data: variable]

[CRC: 4 bytes]

Our file will look like this:

What Is AngeCryption?

AngeCryption is a clever trick introduced by Ange Albertini that allows you to encrypt one valid file into another valid file.

More precisely, it lets you manipulate the plaintext before encryption so that the resulting ciphertext is itself a valid file - just in a different format. You get to choose both:

- the original file you want to hide (e.g. a PDF),

- and the format of the file it will become when encrypted (e.g. a PNG image).

Then, when you decrypt that “disguised” file using the correct key, you recover the original one.

In short, you control both the input and the output of the encryption, which is what makes AngeCryption so unique.

You encrypt a valid file -> get a different valid file -> decrypt it to recover the original

How to Do Angecryption

How does that work? Block ciphers like AES in CBC mode behave like random permutations, normally you can’t predict the output.

Recap: AES-CBC Mode

In CBC (Cipher Block Chaining) mode, encryption works as follows:

C0 = AES(P0 xor IV)

C1 = AES(P1 xor C0)

C2 = AES(P2 xor C1)

...

But in CBC you can choose the Initialization Vector (IV) freely. By setting the IV appropriately, you can force the first block of ciphertext to be anything you want, given any plaintext and key. In practice, this means if you want your encrypted file to start with a valid file header, you can choose an IV so that the first ciphertext blocks matches that header. Albertini’s technique then uses the fact that many formats allow arbitrary “junk” data after the end of file marker, giving enough freedom to adjust the rest of the data.

Angecryption example

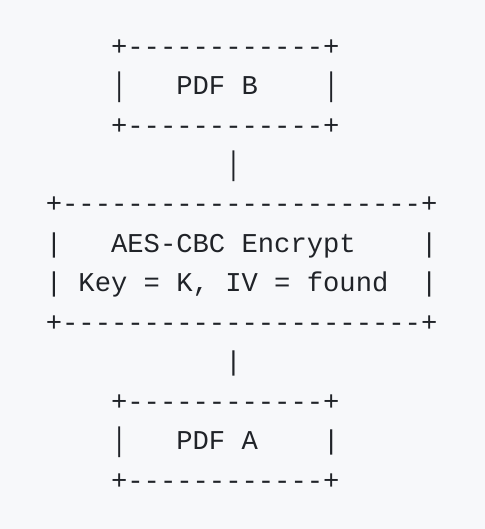

In Angecryption, we aim to hide one file within the encryption of another. Unlike classical encryption, which hides data by transforming it into unreadable ciphertext, Angecryption plays with structure and format interpretation. One concrete example is encrypting a PDF into another PDF - such that the encrypted output is still a valid file in both forms.

Let’s walk through an illustrative example where we encrypt PDF B into PDF A using AES encryption in CBC mode. That means we must choose a secret key and find an IV such that CBC encryption of PDF B “magically” result in PDF A. This is possible because we can influence the output of the first encrypted block by adjusting the IV.

So, each ciphertext block depends on the previous ciphertext and the current plaintext block. To “control” the output ciphertext, we can solve the equation backwards.

IV = EXPECTED xor P0

We can now control the first ciphertext block of our file. But we want to control all the content of our PDF A.

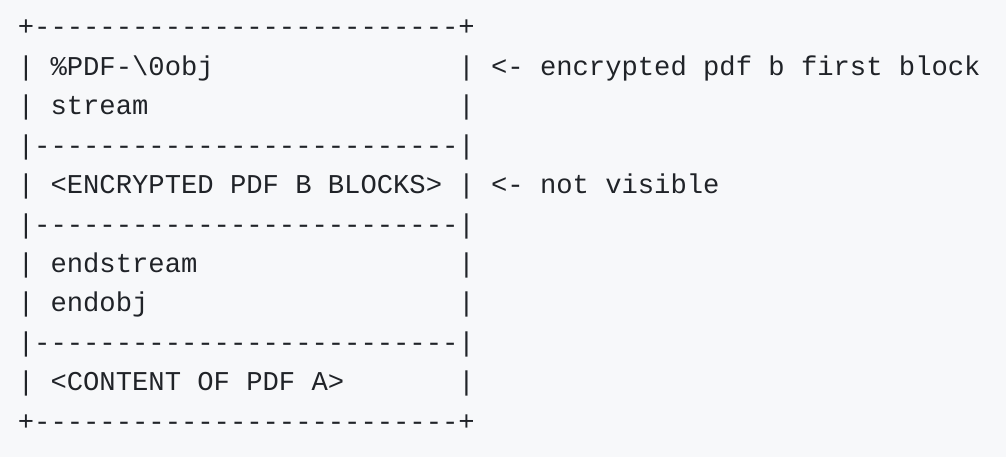

We have to “build” PDF B, so we have to know how a PDF file is structured. A file is recognized as PDF if the first bytes of the files are %PDF-<version> and we can force the first ciphertext so:

IV = b"%PDF-\0obj\nstream" xor P0

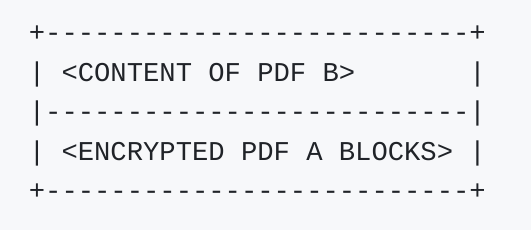

This beginning of the file allows the parser to recognize the file as a pdf, and to open an “anonymous” part of the bytes that won’t be displayed in our final PDF. This part is not displayed, as it contains no valid PDF display instructions. It serves only to satisfy format recognition, and can contain arbitrary data as long as it doesn’t interfere with the rest of the PDF structure. In this anonymous block we add the PDF B encrypted with our key and the IV found.

We can then close our block with : "\nendstreamendobj\n" and the bytes of our PDF A without its header (PDF-<version>).

The parser will read our PDF, understand the header as being the pdf of an unknown version and ignore our anonymous block because it’s not linked to anything. Some parsers like firefox will accept to read the PDF despite the liberties taken on the parser while adobe reader will refuse to read this type of pdf in most cases.

If we decrypt our file thus constructed, we obtain a file with the following configuration.

PDF parsers allow a certain number of dead bytes at the end-of-file (EOF), which will not be parsed by the software. These extra bytes come after the logical end of the PDF, so the PDF can be displayed normally.

Conclusion

Funky files, polyglots, and Angecryption are more than technical curiosities - they are brilliant demonstrations of how flexible, ambiguous, and hackable file formats can be. By understanding how parsers interpret data and how formats tolerate extra or unexpected content, we can craft files that speak multiple “languages” at once.

We’ve only scratched the surface of what’s possible. The best way to learn is to experiment yourself. But remember, with great power comes great responsibility. Manipulating file structures at the binary level can lead to unpredictable behaviors, crashes, or even vulnerabilities if used maliciously.

Now it’s your turn: dig into file specs, open your hex editor, and start bending bytes to your will.