Table of Content

- Introduction

- Notepad: A Concrete Example

- The Internal Mechanisms of Windows

- From Software to Screen: How Display Really Works

- Conclusion

Introduction

In our daily lives, computers play a central role: we use them to work, learn, have fun, and communicate. We all use applications like web browsers (Edge, Google Chrome…), word processors (like Word), or even simple tools like Windows Notepad without really knowing how they work or how the computer displays information on the screen.

The goal of this article is to explain, in a simple and accessible way, how your computer’s applications work “under the hood” on a Windows system. We’ll take a closer look at how a basic application like Notepad displays text and buttons on your screen.

Understanding how your computer displays information isn’t just for professionals. It can help you solve everyday tech problems more easily such as bugs, application crashes, or slowdowns and allows you to use your software more efficiently and with greater confidence. This understanding also makes it easier to determine whether an issue stems from a specific application or from the computer itself. With this knowledge, you may find yourself growing more curious and independent when dealing with technology, and for those interested, it can even serve as a first step towards learning to code or customizing your digital environment.

Notepad: A Concrete Example

Presenting Notepad

Among all the applications on your computer, Notepad is a perfect example to understand how a simple program works. It comes pre-installed on Windows and allows you to write, edit, and save text in files.

Its interface is intentionally simple: a white area to write, a few menus and buttons and that’s it! Because of this simplicity, it’s an ideal case study to learn how a software application displays itself and interacts with the system.

Here’s what Notepad looks like:

How Notepad Builds and Displays Its Graphic Interface

When you doubleclick the Notepad icon on your desktop, Windows runs a program called NOTEPAD.EXE and shows you its window.

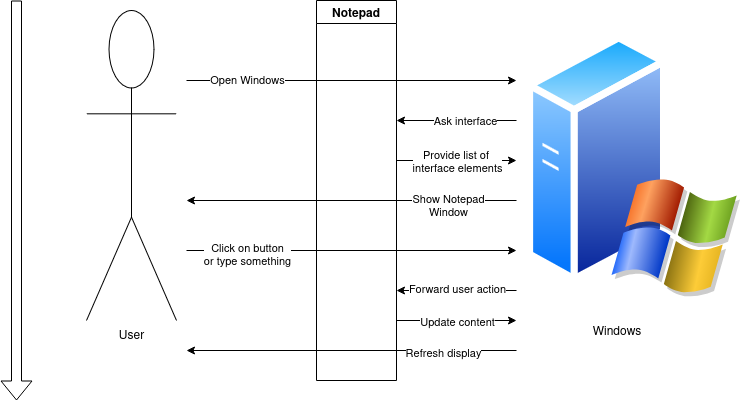

In reality, launching Notepad is a bit like calling a construction manager: the program gives Windows a list of instructions to build the interface (buttons, menus, text areas), and Windows does the actual drawing and display. Here’s how it works:

1. Notepad Describes Its Interface to Windows

At startup, Notepad tells Windows what its window should look like: a menu bar, a large area to write text, and maybe some small buttons. Instead of drawing these elements directly, Notepad sends requests to Windows essentially saying, “I need a text box here, and a menu there.”

2. The Window Manager Takes Over

These requests go to a central part of Windows called the window manager. Its job is to create and manage all the windows on your screen. For example if your browser, File Explorer and Notepad are open at the same time, the window manager decides how to arrange them, how to draw their borders, and how to handle actions like minimizing or closing a window.

3. Windows Builds and Displays the Window

Once it receives the instructions, Windows gets to work.

It uses what are called standard graphical controls (or widgets): for example, a text box, a button, a menu bar.

It places each element in the right location and draws everything on screen.

In summary, Notepad doesn’t draw these elements itself it relies on Windows to assemble and display all the standard components.

When you see Notepad’s window with its white background and blinking cursor, it’s Windows that assembled and drew all those elements based on Notepad’s requests.

4. Interactions Go Through Windows

When you click a menu, type text, or move the window, these actions first go to Windows. Then Windows sends messages to Notepad, saying: “The user clicked here”, “They typed this letter”, “They resized the window”

Notepad reacts by opening a file, updating the text, or showing a popup.

Conclusion for this part

Notepad is mainly responsible for managing the content and internal logic of the text editor, while Windows more specifically, the window manager handles the visual display of all elements on screen and manages the interactions between the user and the application.

This diagram summarizes how Notepad and Windows interact:

The Internal Mechanisms of Windows

Let’s imagine that Notepad wants to display the letter “A” inside its window. How does that actually happen within the system?

In reality, Notepad just like any Windows application, never draws directly to the screen. Instead, it relies on a set of tools provided by the operating system called Graphics APIs.

What Is a Graphics API?

API stands for Application Programming Interface. It’s a collection of functions that applications can call to request services from the operating system such as displaying an image, reading a file, or creating a window.

When we talk about Graphics APIs, we’re referring to the software toolkit Windows provides for drawing visual elements: text, images, windows, menus, buttons…

Rather than manipulating the graphics card directly, the application sends instructions to the API, which handles the implementation: “Display this text here, using this font”, “Draw a window of this size with a menu bar”, “Render a line between these two points”…

This abstraction makes it easier for developers to build rich user interfaces without having to deal with hardware specific details.

2. Window Management: A Core Component

Among the many services offered by Windows graphics API, window management plays a central role. When an application like Notepad requests a new window, it doesn’t build it manually. Instead, it calls the API, which:

- Creates a kind of internal digital “blueprint” (stored in memory) that describes what the window should look like, its position, buttons, and content.

- Assigns it a unique identifier (called an

HWND, or Handle to a Window) - Manages all aspects of the window: its position, size, appearance, and behavior (minimize, close, move…)

This work is handled by a specialized component of the graphics API: the Window Manager. Its job is to coordinate the display and behavior of all system windows.

For instance, the Window Manager determines which window is currently in the foreground, which one receives keyboard or mouse input and how windows are stacked, shown, or hidden. Without this component, windows couldn’t exist or interact properly with the user.

3. Examples of Graphics APIs on Windows

Windows supports several Graphics APIs, each with its own capabilities and use cases:

- GDI (Graphics Device Interface): This is the legacy API, used since the early versions of Windows. It can render text, draw lines, and handle basic 2D graphics. Notepad still relies heavily on GDI.

- Direct2D / DirectWrite: These are modern APIs that use the power of your computer’s graphics card (GPU) to speed up drawing and display. This “GPU acceleration” means they can handle complex graphics and smooth animations much more efficiently, and produce high quality text.

- Direct3D: Used for rendering 3D graphics. It’s the API used for video games, modeling applications, and advanced visual effects in modern user interfaces.

4. Windows Messages: How User Interaction Is Handled

When a user clicks a button, types text, or resizes a window, the application doesn’t directly detect these actions. Instead, Windows captures these events and translates them into messages.

A message is a small data structure that Windows sends to a window to notify it of something: “The user pressed a key”, “The mouse entered the window”, “You need to redraw the central area of the window”.

These messages are fundamental to how the Windows graphical system operates. Every window has a kind of “inbox” where Windows places incoming messages just like a notification center.

Example:

Let’s say you click inside the Notepad window:

- Windows detects a mouse click event.

- It sends a

WM_LBUTTONDOWN(Left Button Down) message to the appropriate window. - Notepad receives this message and decides how to respond by activating the text area, moving the cursor, or opening a menu.

5. The Message Loop: A Core Component of Any Windows App

To function properly, every Windows application constantly listens for incoming messages. This is known as the message loop.

A typical message loop looks like this:

|

|

(Don’t worry if this looks a bit mysterious or complicated right now. In the next part, we’ll explain exactly what each part of this loop does, step by step!)

What exactly does this loop do?

Once the application is launched, it enters a continuous cycle with three main steps:

1. Receive a message:

Windows places user events (like mouse clicks, key presses, or resize requests) into a queue. The app calls GetMessage to retrieve the next event.

2. Interpret the message:

TranslateMessage can convert codes into more meaningful data for example, transforming “key code 65” into the letter “A”.

3. React to the message:

DispatchMessage sends the message to a dedicated function (usually called the window procedure), where the app decides what to display a character, open a menu, or redraw a section of the screen.

Why Is the Message Loop So Important?

The message loop allows the application to respond to user actions like typing, remain responsive even when multiple events happen at once, and stay idle (not consuming CPU) when nothing is happening.

You can think of the message loop as a switchboard operator: it waits for calls (messages), interprets them, and routes them to the right “person” inside the app to handle the request.

Conclusion for this part

Thanks to graphics APIs, the window manager, the message system, and the message loop, Windows provides a structured, efficient, and interactive framework that allows each application to display its interface, respond to user input, and interact seamlessly with the system.

From Software to Screen: How Display Really Works

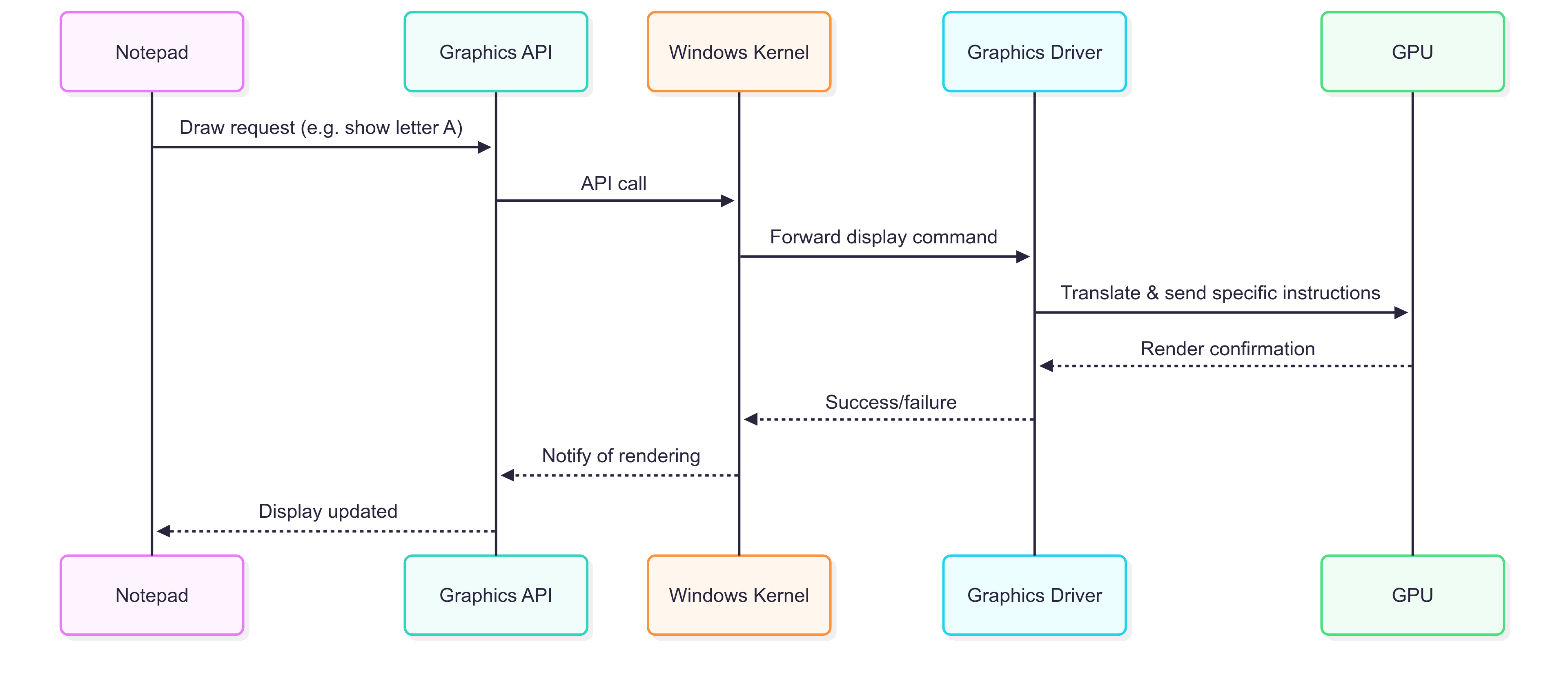

Now that we understand how a program sends its display requests to Windows in order to show graphical elements, one question remains: How does the computer actually transform these instructions into visible pixels on the screen?

For the image to appear, two main components are involved: the Windows kernel and the graphics drivers.

What is the Windows Kernel?

The Windows kernel is the core of the operating system. It’s what makes the entire machine work: without it, no program would run, no file could be read, and not a single pixel would ever appear on your screen.

But what exactly does it do? The kernel is responsible for everything related to:

- Processor management (deciding which program runs and when),

- Memory management (controlling who can access which area of RAM),

- Device communication (with peripherals like the keyboard, mouse, hard drive, and graphics card).

What about display operations? When a program, such as Notepad, wants to show something on the screen, it first calls a graphics API (like GDI or Direct2D). But this API doesn’t communicate directly with the graphics card: every request is relayed through the Windows kernel.

The kernel’s responsibilities here are threefold:

- Organize the requests (so everything happens in the correct order),

- Protect the system by ensuring that no program does anything forbidden,

- Forward the command to the graphics driver, which knows exactly how to interact with the hardware.

The kernel acts as the bridge between the software world (like Notepad) and the hardware world (such as the graphics card), keeping everything secure and under control.

A practical example: Suppose you open a new window. Here’s what the kernel does behind the scenes:

- It allocates memory to store information for the new window, he schedules the processor to prepare for its display

- It coordinates actions with the window manager

- It sends commands to the driver so the graphics card can render the required pixels

- It continuously monitors the process for errors or conflicts even while dozens of other windows might be moving around at the same time.

What is a Graphics Driver?

A graphics driver is a highly specialized piece of software. Its role is to serve as a translator between Windows and your computer’s graphics card.

But why do we need a translator? Because there are hundreds of different graphics cards out there: from different brands (NVIDIA, AMD, Intel…), with different architectures, and varying performance levels. It’s simply impossible for Windows to know the technical details of every single card. So, instead, Windows sends generic instructions, such as: “Display this image here,” “Draw a blue line there”, “Redraw this window.”

The graphics driver receives these standardized commands and then:

- It translates them into the specific language that the graphics card understands,

- It optimizes their execution to make the most of the hardware’s capabilities,

- It sends the appropriate instructions directly to the card.

It’s a bit like Windows saying, “I’d like a coffee,” and the driver replying, “All right, for your X200 capsule machine, you need to press here, preheat for 4 seconds, and add hot water at 87 °C.”

Without a driver, even the most powerful graphics card is useless. And a good driver can make a real difference: better graphics, smoother performance, and fewer bugs.

The following diagram illustrates the full chain of display processing:

Conclusion

Step by step, we’ve uncovered what really happens “under the hood” when an application displays information on your screen. Starting with a straightforward program like Notepad, we’ve traced the entire journey: from how an application describes its interface to Windows without having to manage every pixel itself to the critical role of graphics APIs that act as universal translators between software and the operating system. We’ve seen how Windows intelligently manages window display, coordinating multiple programs so they can share the screen seamlessly, and how it efficiently handles the flow of messages that keep your computer responsive to every interaction. Finally, we’ve revealed how the Windows kernel and graphics drivers work in tandem, ensuring the graphics card faithfully renders precisely what the application intended.

Gaining this kind of insight even for those who aren’t IT specialists is far from trivial. It makes diagnosing bugs and bottlenecks easier, helps you use and understand your computer with greater confidence, opens doors (for the curious) to programming, customization, or simply stronger control over your digital environment, and enables more informed decisions when it comes to hardware or software choices. This understanding isn’t reserved for “geeks” it allows everyone to interact meaningfully with technology, and to feel empowered to tweak, experiment, or resolve many everyday issues on their own.

So, the next time you launch Notepad or any other application you’ll know that behind the scenes, a hidden cast of actors is working methodically to make your text appear, almost as if by magic. In the end, technology is less mysterious and much simpler once you grasp its fundamentals now it’s your turn to take advantage of that knowledge!

Bibliography

-

Microsoft.

Windows GDI - Windows Apps Documentation.

The official documentation of GDI -

Kyle Halladay.

Rendering With Notepad, 2020.

An article that explores how to create a raytracing system by modifying the Windows Notepad application, demonstrating how GDI functions can be leveraged for custom graphics rendering. -

YouTube: Sebastien Lagarde.

“How Notepad.exe Renders Text - Windows Graphics Internals Explained”.

A brief video explaining how Windows’ native graphics APIs are used internally by applications like Notepad.exe for rendering